There’s an interesting divergence between the extreme complexity of the predicament that besets contemporary industrial civilization, on the one hand, and the remarkable simplicity of the failures of reasoning that have sent us hurtling face first into that predicament, on the other. Nearly all of those failures share a common root, which is the inability—or at least the unwillingness—of most people in the modern world to pay attention to the natural cussedness of whole systems.

The example I have in mind just at the moment runs all through one of the most lively nondebates in today’s media, which is about peak oil. I call it a nondebate because those who are trying to debate the issue—that is to say, those people who have noticed the absurdity of trying to extract infinite amounts of petroleum from a finite planet—are by and large shut out of the discussion. Those who hold the other view, for their part, aren’t debating. With embarrassingly few exceptions, instead, they’re merely insisting at the top of their lungs that peak oil has been disproved by some glossy combination of short term factors, speculative bubbles, and overblown hype about the future, and can we please just get back to our lifestyles of mindless consumption and waste?

Behind the cornucopian handwaving, though, is a real debate, one that those of us who are aware of peak oil need to address. The issue at the heart of the debate is the shape of the curve that will define future petroleum production worldwide, and the reason that it needs to be addressed is that so far, at least, that curve is not doing what most peak oil theories say it should do.

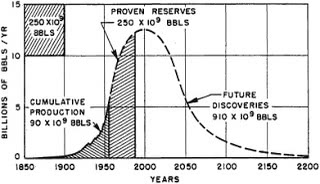

The original version of the peak oil curve, of course, is the one sketched out by M. King Hubbert in his famous 1956 paper. Here it is:

That’s the model that underlies most of today’s peak oil analyses. It’s a good first approximation of the way that oil production normally rises and falls over time on any scale—a well, a field, an oil province, a country—provided that external factors don’t interfere. The problem here, of course, is that oil production doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and so external factors always interfere. It helps to rephrase that last point in systems terms: the production of oil takes place within a whole system and is always influenced by the state of the system. That’s why at best, the history of oil production from any given well, field, oil province, or country only roughly approximates the ideal shape of the Hubbert curve, and many real-world examples stray all over the map in their wanderings from the zero point at the beginning to the one at the end.

It’s the failure to appreciate this point that has left a good many peak oil analysts flailing when global petroleum production failed to decline according to some predicted schedule. Anyone who’s been following the peak oil blogosphere for more than a few years has gotten used to the annual predictions—they tend to pop up like mushrooms every December—that the year about to begin would finally see rates of petroleum production begin dropping like the proverbial rock. Tolerably often, in fact, the same predictions get recycled from one year to the next, with no more attention to the lessons of past failure than you’ll find in one of Harold Camping’s Rapture prophecies. Even among those who don’t go that far out on a limb, the notion that global production of petroleum ought to start dropping steeply sometime soon is all but hardwired into the peak oil scene.

The peak of global conventional petroleum production arrived, as I hope most of my readers are aware by now, in 2005. The seven years since then have given us a first glimpse at the far end of Hubbert’s curve, and so far, it’s not following the model. Conventional petroleum production has declined, and the price of oil has wobbled unsteadily up to levels that mainstream analysts considered impossible a decade ago; that much of the peak oil prophecy has been confirmed by events. Overall production of liquid fuels, though, has remained steady and even risen slightly, as high prices have made it profitable for unconventional petroleum and a range of petroleum substitutes—tar sand extractives, natural gas liquids, biodiesel, ethanol, and the like—to be poured into the world’s fuel tanks.

It’s only fair to note that this was among the predictions made by critics of peak oil theory back when that was still a subject of debate. The standard argument economists used to dismiss the threat of peak oil was precisely that rising prices would make other energy sources economical, following the normal workings of supply and demand. For all its flaws—and I plan on dissecting a few of those shortly—that prediction was rooted in the behavior of whole systems.

The law of supply and demand, in fact, is one manifestation of a basic principle of systems theory, a principle pervasive and inescapable enough that it’s not unreasonable to call it a law. The law of equilibrium, as we might as well call it, states that any attempt to change the state of a whole system will set in motion coutervailing processes that tend to restore the system to its original state. Those processes will not necessarily succeed; they may fail, and they may also trigger changes of their own that push the system in unpredictable directions; still, such processes always emerge, and if you ignore them, it’s a fairly safe bet that they’re going to blindside you.

The law of equilibrium is what’s behind so many of the failures of technological progress in recent years. Decide that you can just go ahead and annihilate pathogenic microbes en masse with antibiotics, for example, and the countervailing processes of the planet’s microbial ecology are going to shift into high gear, churning out genes for antibiotic resistance that spread from one bacterial species to another and render antibiotics less effective with every year that passes. The same is true of genetically engineered plants—one of the ugly little secrets of the GMO industry is that one insect species after another is doing exactly what Darwinian theory says it should, evolving right around the biotoxins released by Monsanto’s supposedly pestproof Frankencrops, and chowing down on the otherwise unprotected buffet spread for them by unsuspecting farmers—and of any number of equally clueless tinkerings with natural processes that are blowing up in humanity’s collective face just now.

The global industrial economy is also a whole system, and though it’s countless orders of magnitude less complex and sophisticated than the biosphere, it still responds to changing conditions with its own countervailing processes. That’s what’s been happening with global liquid fuels production. As the rate of conventional petroleum production peaked and began its decline, the countervailing processes took the form of rising prices, which made more expensive sources of liquid fuels profitable, and kept total production of liquid fuels not far from where it was when conventional oil peaked in 2005. The wild swings in price since then have provided the thermostat for this homeostatic process, balancing the ragged decline of conventional petroleum and the equally ragged expansion of substitute fuels by influencing the profitability of any given fuel over time. In its own way, it’s an elegant mechanism, however much turmoil and suffering it happens to generate in the real world.

Does this mean that peak oil is no longer an issue? Not by a long shot, because the economic shifts necessary to bring substitute fuels into the fuel supply don’t exist in a vacuum, either. They also put pressure on the global industrial economy, and generate countervailing processes of their own. That’s the detail that both sides of the peak oil nondebate have by and large been missing, even as those countervailing processes have been whipsawing the global economy and driving changes that seemed implausible even to most peak oil analysts just a short time ago.

The point that has to be grasped in order to understand these broader effects is that the higher price of substitute fuels isn’t arbitrary. Tar sand extractives, for example, cost more to produce than light sweet crude because pressure-washing tar out of tar sands and converting it to a rough equivalent of crude oil takes much more in the way of energy, resources, and labor than it takes to drill for the same amount of conventional oil. Each year, therefore, as more of the liquid fuels supply is made up by tar sand extractives and other substitute fuels, larger fractions of the annual supply of energy, raw materials, and labor have to be devoted to the process of bringing liquid fuels to market, leaving a smaller portion of each of these things to be divided up among all other economic sectors.

Some of the effects of this process are obvious enough—for example, the spikes in food prices we’ve been having since 2005, as the increasing use of ethanol and biodiesel as liquid fuels means that grains and vegetable oils are being diverted from the food supply for use as feedstocks for fuel. Many others are less obvious—for example, as energy prices have risen and energy companies have become Wall Street favorites, many billions of dollars that might otherwise have become capital for other industries have flowed into the energy sector instead. Each of these effects, however, represents a drain on other sectors of the economy, and thus a force for change that sets countervailing processes into motion.

Those processes are a good deal more complex than the ones we’ve traced so far, since they involve competition for capital and other resources among different sectors of the economy, a struggle in which political and cultural factors play at least as large a role as economics. Still, one result can be traced in the unexpected decline in petroleum consumption that has taken place in the United States since 2008, and that precisely parallels the similar decline that happened between 1975 and 1985 in response to a similar rise in oil prices. To describe this process as demand destruction is an oversimplification; a dizzyingly complex array of factors, ranging from the TSA’s officially sanctioned habit of sexually molesting airline passengers, on the one hand, to shifts in teen fashion that are making driving uncool for the first time in a century on the other, have fed into the decline in oil consumption; still, the thing is happening, and it’s probably fair to say that the increasing impoverishment of most Americans is playing a very large role in it.

Thus the simple model of peak oil that dates from Hubbert’s time badly needs updating. Ironically, The Limits to Growth—the most accurate and thus, inevitably, the most maligned of the various guides to our unwelcome future offered up so far—provided the necessary insight decades ago. By the simple expedient of lumping resources, industrial production, and other primary factors into a single variable each, the Limits to Growth team avoided the fixation on detail that so often blinds people to systems behavior on the broad scale. Within the simplified model that resulted, it became obvious that limitless growth on a finite planet engenders countervailing processes that tend to restore the original state of the system. It became just as obvious that the most important of those processes was the simple fact that in any environment with finite resources and a finite capacity to absorb pollution, the costs of growth would eventually rise faster than the benefits, and force the global economy to its knees.

That’s what’s happening now. What makes that hard to see at first glance is that the costs of growth are popping up in unexpected places; put too much stress on a chain and it’ll break, but the link that breaks isn’t necessarily the one closest to the source of stress. The economies of the world’s industrial nations are utterly dependent on a steady supply of liquid fuels, and so a steady supply of liquid fuels they will have, even if every other sector of the economy has to be dumped into the hopper in order to keep the fuel flowing. As every other sector of the economy is dumped into that hopper, in turn, the demand for liquid fuels goes down, because when people who used to be employed by the rest of the economy can no longer afford to spend spring break in Mazatlan, or buy goods that have to be shipped halfway around the planet, or put gas in their cars, their share of petroleum consumption goes unclaimed.

This process is, among other things, one of the main forces behind the disappearance of "bankable projects" discussed in last week’s post. The reallocation of ever larger fractions of capital, resources, and labor to the production of liquid fuels represents a subtle drain on most other fields of economic endeavor, driving costs up and profits down across the board. The one exception is the financial sector, since increasing the amount of paper value produced by purely financial transactions involves no additional capital, resources, and labor—a derivative worth ten million dollars costs no more to produce, in terms of real inputs, than one worth ten thousand, or for that matter ten cents. Thus financial transactions increasingly become the only reliable source of profit in an otherwise faltering economy, and the explosive expansion of abstract paper wealth masks the contraction of real wealth.

When systems theorists explain that the behavior of whole systems can be counterintuitive, this is the sort of thing they have in mind. It’s quite possible that as we move further past the peak of conventional petroleum production, the consumption of petroleum products will continue to decline, so that when the ability to produce substitute fuels declines as well—as of course it will—the impact of the latter decline will be hard to trace. Ever more elaborate towers of hallucinatory wealth, ably assisted by reams of doctored government statistics, will project the illusion of a thriving economy onto a society in freefall; the stock market will wobble around its current level for a long time to come, booming and crashing on occasion as bubbles come and go; meanwhile a growing fraction of the population will be forced to drop out of the official economy altogether, and be left to scrape together whatever sort of living they can in some updated equivalent of the Hoovervilles and tarpaper shacks of the 1930s.

No doubt the glossy magazines that make their money by marketing a rose-colored image of the future to today’s privileged classes will hail declines in petroleum demand as a sign that some golden age of green technology is at hand, and trot out a flurry of anecdotes to prove it; all they’ll have to do is ignore the hard figures showing that demand for renewable-energy systems is dropping too, as people who have no money find solar panels as unaffordable as barrels of oil. For that matter, the people who are insisting in today’s media that the United States will achieve energy independence by 2050 may just turn out to be right; it’s just that this will happen because the US will have devolved into a bankrupt Third World nation in which the vast majority of the population lives in abject poverty and petroleum consumption has dropped to a sixth or less of its current level.

That’s not the future that comes out of a simplistic reading of Hubbert’s curve—though it’s only fair to mention that it’s the future that some of us who used to be on the fringes of the peak oil scene have been discussing all along. Still, it looks increasingly likely that this is the sort of future we’re going to get, and it’s certainly the one that current trends appear to be creating around us right now. No doubt cornucopians in 2050 will be insisting that everything is actually just fine, the drastic impoverishment of most of the American people is just the sort of healthy readjustment a capitalist economy needs from time to time, and we’ll be going back to the Moon any day now, just as soon as we finish reopening the Erie Canal to mule-drawn barge traffic so that grain can get from the Midwest to the slowly drowning cities of the east coast. With any luck, though, the peak oil blogosphere—it’ll have morphed into printed newsletters by then, granted—will have long since noticed that whole system processes do in fact shape the way that the twilight of the petroleum age is unfolding. How that is likely to affect the twilight of American empire will be central to the posts of the next several months.

****************

End of the World of the Week #28

It’s a repeated source of embarrassment for scientists of all kinds that the culture in which they live is so much less comfortable with hypothetical statements and tentative suggestions than the internal subculture of science tends to be. Witness the embarrassment of the solar astronomers and atmospheric physicists who suggested, back in the late 1990s, that the upcoming solar cycle 23 might see some disruption of Earth-based electronics by the electromagnetic effects of solar flares.

It was a reasonable supposition, since strong solar flares have a solid track record of frying sensitive electronic systems and disabling satellites. Still, it didn’t take long before their tentative suggestion was inflated into apocalyptic prophecy. Web pages screamed that before cycle 23 was over, an immense solar flare would inevitably bring down the electrical grid worldwide, turning computers and other electronic devices into useless silicon fritters, and plunging the world into an instant dark age complete with roving hordes of starving survivors. The popular online sport of apocalypse machismo—"I can imagine a cataclysm more horrifying than you can!"—went into overdrive on this one, spawning no end of highly colored accounts of just how everybody else was going to die.

As it happened, cycle 23 did see a couple of spectacular solar flares, including two of the largest ever measured, but none of the big ones happened to be pointed anywhere near Earth. (If the Earth’s orbit was as big around as a football stadium, remember, the Sun would be a beach ball sitting on the 50 yard line and the Earth would be a marble perched somewhere on the last row of bleachers.) When solar cycle 23 came to an end in December 2008, as a result, the Sun shone down on a world not noticeably more devastated than it had been when the cycle began.