Over the nearly seven years I’ve spent blogging on

The Archdruid Report, the themes of my weekly posts have veered back and forth between pragmatic ways to deal with the crisis of our time and the landscape of ideas that give those steps their meaning. That’s been unavoidable, since what I’ve been trying to communicate here is as much a way of looking at the world as it is a set of practices that unfold from that viewpoint, and a set of habits of observation that focus attention on details most people these days tend to ignore.

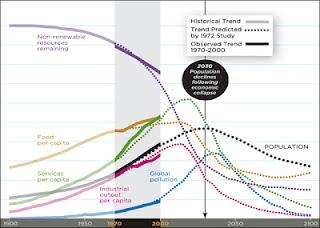

There’s a lot more that could be said about the practical side of a world already feeling the pressures of peak oil, and no doubt I’ll contribute to that conversation again as we go. For now, though, I want to move in a different direction, to talk about what’s probably the most explosive dimension of the crisis of our time. That’s the religious dimension—or, if you prefer a different way of speaking, the way that our crisis relates to the fundamental visions of meaning and value that structure everything we do, and don’t do, in the face of a troubled time.

There are any number of ways we could start talking about the religious dimensions of peak oil and the end of the industrial age. The mainstream religions of our time offer one set of starting points; my own Druid faith, which is pretty much as far from the mainstream as you can get, offers another set; then, of course, there’s the religion that nobody talks about and most people believe in, the religion of progress, which has its own dogmatic way of addressing such issues.

Still, I trust that none of my readers will be too greatly surprised if I choose a starting point a little less obvious than any of these. To be specific, the starting point I have in mind is a street scene in the Italian city of Turin, on an otherwise ordinary January day in 1889. Over on one side of the Piazza Carlo Alberto, at the moment I have in mind, a teamster was beating one of his horses savagely with a stick, and his curses and the horse’s terrified cries could be heard over the traffic noise. Finally, the horse collapsed; as it hit the pavement, a middle-aged man with a handlebar mustache came sprinting across the plaza, dropped to his knees beside the horse, and flung his arms around its neck, weeping hysterically. His name was Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, and he had just gone hopelessly insane.

At that time, Nietzsche was almost completely unknown in the worlds of European philosophy and culture. His career had a brilliant beginning—he was hired straight out of college in 1868 to teach classical philology at the University of Basel, and published his first significant work,

The Birth of Tragedy, four years later—but strayed thereafter into territory few academics in his time dared to touch; when he gave up his position in 1879 due to health problems, the university was glad to see him go. His major philosophical works saw print in small editions, mostly paid for by Nietzsche himself, and were roundly ignored by everybody. There were excellent reasons for this, as what Nietzsche was saying in these books was the last thing that anybody in Europe at that time wanted to hear.

Given Nietzsche’s fate, there’s a fierce irony in the fact that the most famous description he wrote of his central message is put in the mouth of a madman. Here’s the passage in question, from The Joyous Science (1882):

Haven’t you heard of the madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran into the marketplace, and shouted over and over, ‘I’m looking for God! I’m looking for God!’ There were plenty of people standing there who didn’t believe in God, so he caused a great deal of laughter. ‘Did you lose him, then?’ asked one. ‘Did he wander off like a child?’ said another. ‘Or is he hiding? Is he scared of us? Has he gone on a voyage, or emigrated?’ They shouted and laughed in this manner. The madman leapt into their midst and pierced him with his look.‘Where is God?’ he shouted. ‘I’ll tell you. We’ve killed him, you and I! We are all his murderers. But how could we have done this? How could we gulp down the oceans? Who gave us a sponge to wipe away the whole horizon? What did we do when we unchained the earth from the sun? Where is it going now? Where are we going now? Away from all suns? Aren’t we falling forever, backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions at once? Do up and down even exist any more? Aren’t we wandering in an infinite void? Don’t we feel the breath of empty space? Hasn’t it become colder? Isn’t night coming on more and more all the time? Shouldn’t we light lanterns in the morning? Aren’t we already hearing the sounds of the gravediggers who are coming to bury God? Don’t we smell the stink of a rotting God—for gods rot too?‘God is dead, God remains dead, and we have killed him. How can we, the worst of all murderers, comfort ourselves? The holiest and mightiest thing that the world has yet possessed has bled to death beneath our knives!’

Beyond the wild

imagery—which was not original to Nietzsche, by the way; several earlier German writers had used the same metaphor before he got to it—lay a precise and trenchant insight. In Nietzsche’s time, the Christian religion was central to European culture in a way that’s almost unthinkable from today’s perspective. By this I don’t simply mean that a much greater percentage of Europeans attended church then than now, though this was true; nor that Christian narratives, metaphors, and jargon pervaded popular culture to such an extent that you can hardly make sense of the literature of the time if you don’t know your way around the Bible and the standard tropes of Christian theology, though this was also true.

The centrality of Christian thought to European culture went much deeper than that. The core concepts that undergirded every dimension of European thought and behavior came straight out of Christianity. This was true straight across the political spectrum of the time—conservatives drew on the Christian religion to legitimize existing institutions and social hierarchies, while their liberal opponents relied just as extensively on Christian sources for the ideas and imagery that framed their challenges to those same institutions and hierarchies. All through the lively cultural debates of the time, values and ethical concepts that could only be justified on the basis of Christian theology were treated as self-evident, and those few thinkers who strayed outside that comfortable consensus quickly found themselves, as Nietzsche did, talking to an empty room.

It’s indicative of the tenor of the times that even those thinkers who tried to reject Christianity usually copied it right down to the fine details. Thus the atheist philosopher Auguste Comte (1798-1857), a well known figure in his day though almost entirely forgotten now, ended up launching a “Religion of Humanity” with a holy trinity of Humanity, the Earth, and Destiny, a calendar of secular saints’ days, and scores of other borrowings from the faith he thought he was abandoning. He was one of dozens of figures who attempted to create ersatz pseudo-Christianities of one kind or another, keeping most of the moral and behavioral trappings of the faith they thought they were rejecting. Meanwhile their less radical neighbors went about their lives in the serene conviction that the assumptions their culture had inherited from its Christian roots were eternally valid.

The only difficulty this posed that a large and rapidly growing fraction of 19th-century Europeans no longer believed the core tenets of the faith that structured their lives and their thinking. It never occurred to most of them to question the value of Christian ethics, the social role of Christian institutions, or the sense of purpose and value they and their society had long derived from Christianity; straight across the spectrum of polite society, everyone agreed that good people ought to go to church, that missionaries should be sent forth to eradicate competing religions in foreign lands, and that the world would be a much better place if everybody would simply follow the teachings of Jesus, in whatever form those might most recently have been reworked for public consumption. It was simply that a great many of them could no longer find any reason to believe in such minor details as the existence of God.

Even those who did insist loudly on this latter point, and on their own adherence to Christianity, commonly redefined both in ways that stripped them of their remaining relevance to the 19th-century world. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the philosopher whose writings formed the high water mark of western philosophy and also launched it on its descent into decadence, is among many other things the poster child for this effect. In his 1793 book Religion Within The Limits of Bare Reason, Kant argued that the essence of religion—in fact, the only part of it that had real value—was leading a virtuous life, and everything else was superstition and delusion.

The triumph of Kant’s redefinition of religion was all but total in Protestant denominations, up until the rise of fundamentalism at the beginning of the 20th century, and left lasting traces on the leftward end of Catholicism as well. To this day, if you pick an American church at random on a Sunday morning and go inside to listen to the sermon, your chances of hearing an exhortation to live a virtuous life, without reference to any other dimension of religion, are rather better than one in two. The fact remains that Kant’s reinterpretation has almost nothing in common with historic Christianity. To borrow a phrase from a later era of crisis, Kant apparently felt that he had to destroy Christianity in order to save it, but the destruction was considerably more effective than the salvation turned out to be. Intellects considerably less acute than Kant’s had no difficulty at all in taking his arguments and using them to suggest that living a virtuous life was not the essence of religion but a suitably modern replacement for it.

Even so, public professions of Christian faith remained a social necessity right up into the 20th century. There were straightforward reasons for this; even so convinced an atheist as Voltaire, when guests at one of his dinner parties spoke too freely about the nonexistence of God, is said to have sent the servants away and then urged his friends not to speak so freely in front of them, asking, “Do you want your throats cut tonight?” Still, historians of ideas have followed the spread of atheism through the European intelligentsia from the end of the 16th century, when it was the concern of small and secretive circles, to the middle of the 18th, when it had become widespread; spreading through the middle classes during of the 18th century and then, in the 19th—continental Europe’s century of industrialization—into the industrial working classes, who by and large abandoned their traditional faiths when they left the countryside to take factory jobs.

By the time Nietzsche wrote God’s epitaph, in other words, the core claims of Christianity were taken seriously only by a minority of educated Europeans, and even among the masses, atheism and secular religions such as Marxism were spreading rapidly at the expense of the older faith. Despite this, however, habits of thought and behavior that could only be justified by the basic presuppositions of Christianity stayed welded in place throughout European sociery. It was as though, to coin a metaphor that Nietzsche might have enjoyed, one of the great royal courts of the time busied itself with all the details of the king’s banquets and clothes and bedchamber, and servants and courtiers hovered about the throne waiting to obey the king’s least command, even though everyone in the palace knew that the throne was empty and the last king had died decades before.

To Nietzsche, all this was incomprehensible. The son and grandson of Lutheran pastors, raised in an atmosphere of more than typical middle-class European piety, he inherited a keen sense of the internal logic of the Christian faith—the way that every aspect of Christian theology and morality unfolds step by step from core principles clearly defined in the historic creeds of the early church.

It’s not an accident that the oldest and most broadly accepted of these, the Apostle’s Creed, begins with the words

“I believe in God the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.” Abandon that belief, and none of the rest of it makes any sense at all.

“I believe in God the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.” Abandon that belief, and none of the rest of it makes any sense at all.

This was what Nietzsche’s madman, and Nietzsche himself, were trying to bring to the attention of their contemporaries. Unlike too many of today’s atheists, Nietzsche had a profound understanding of juast what it was that he was rejecting when he proclaimed the death of God and the absurdity of faith. To abandon belief in a divinely ordained order to the cosmos, he argued, meant surrendering any claim to objectively valid moral standards, and thus stripping words like “right” and “wrong” of any meaning other than personal preference. It meant giving up the basis on which governments and institutions founded their claims to legitimacy, and thus leaving them no means to maintain social order or gain the obedience of the masses other than the raw threat of violence—a threat that would have to be made good ever more often, as time went on, to maintain its effectiveness. Ultimately, it meant abandoning any claim of meaning, purpose, or value to humanity or the world, other than those that individual human beings might choose to impose on the inkblot patterns of a chaotic universe.

I suspect that many, if not most, of my readers will object to these conclusions. There are, of course, many grounds on which such objections could be raised. It can be pointed out, and truly, that there have been plenty of atheists whose behavior, on ethical grounds, compares favorably to that of the average Christian, and some who can stand comparison with Christian saints. On a less superficial plane, it can be pointed out with equal truth that it’s only in a distinctive minority of ethical systems—that of historic Christianity among them—that ethics start from the words “thou shalt” and proceed from there to the language of moral exhortation and denunciation that still structures Western moral discourse today. Political systems, it might be argued, can work out new bases for their claims to legitimacy, using such concepts as the consent of the governed, while claims of meaning, purpose and value can be refounded on a variety of bases that have nothing to do with an objective cosmic order imposed on it by its putative creator.

All this is true, and the history of ideas in the western world over the last few centuries can in fact be neatly summed up as the struggle to build alternative foundations for social, ethical, and intellectual existence in the void left behind by Europe’s gradual but unremitting abandonment of Christian faith. Yet this simply makes Nietzsche’s point for him, for all these alternative foundations had to be built, slowly, with a great deal of trial and error and no small number of disastrous missteps, and even today the work is by no means anything like as solid as some of its more enthusiastic proponents seem to think. It has taken centuries of hard work by some of our species’ best minds to get even this far in the project, and it’s by no means certain even now that their efforts have achieved any lasting success.

A strong case can therefore be made that Nietzsche got the right answer, but was asking the wrong question. He grasped that the collapse of Christian faith in European society meant the end of the entire structure of meanings and values that had God as its first postulate, but thought that the only possible aftermath of that collapse was a collective plunge into the heart of chaos, where humanity would be forced to come to terms with the nonexistence of objective values, and would finally take responsibility for their own role in projecting values on a fundamentally meaningless cosmos; the question that consumed him was how this could be done.

A great many other people in his time saw the same possibility, but rejected it on the grounds that such a cosmos was unfit for human habitation. Their question, the question that has shaped the intellectual and cultural life of the western world for several centuries now, is how to find some other first postulate for meaning and value in the absence of faith in the Christian God.

They found one, too—one could as well say that one was pressed upon them by the sheer force of events. The surrogate God that western civilization embraced, tentatively in the 19th century and with increasing conviction and passion in the 20th, was progress. In our time, certainly, the omnipotence and infinite benevolence of progress have become the core doctrines of a civil religion as broadly and unthinkingly embraced, and as central to contemporary notions of meaning and value, as Christianity was before the Age of Reason.

That in itself defines one of the central themes of the predicament of our time. Progress makes a poor substitute for a deity, not least because its supposed omnipotence and benevolence are becoming increasingly hard to take on faith just now. There’s every reason to think that in the years immediately before us, that difficulty is going to become impossible to ignore—and the same shattering crisis of meaning and value that the religion of progress was meant to solve will be back, adding its burden to the other pressures of our time.