This is the fourteenth installment of an exploration of some of the possible futures discussed on this blog, using the toolkit of narrative fiction. Our narrator returns from his trip to a tier one county full of doubts about the Lakeland Republic’s prospects, and has those at once challenged and sharpened by a conversation at the local Atheist Assembly...

***********

I’d had lunch with Ruth Mellencamp at a pleasant little diner a block from the station before I caught the train, so I had nothing to do until I got to Defiance but watch farmland roll by and think about what I’d seen since I’d crossed the border less than a week before. My reactions were an odd mix of reluctant admiration and unwilling regret. The people of the Lakeland Republic had taken a situation that would have crushed most countries—an international embargo backed up with repeated attempts at regime change—and turned it into their advantage, using isolation from the capital flows and market pressures of the global economy to give them space to return to older ways of doing things that actually produced better results than the modern equivalents.

The problem with that, I told myself, was that it couldn’t last. That was the thing that had bothered me, the night after I’d toured the New Shaker settlement, though it had taken another day to come into focus. The whole Lakeland Republic was like the New Shakers, the sort of fragile artificial construct that only worked because it isolated itself from the rest of the world. Now that the embargo was over and the borders with the other North American republics were open, the isolation was gone, and I didn’t see any reason to think the Republic’s back-to-the-past ideology would be strong enough by itself in the face of the overwhelming pressures the global economy could bring to bear.

That wasn’t even the biggest challenge they faced, though. The real challenge was progress—the sheer onward momentum of science and technology in the rest of the world. Sure, I admitted, the Lakeland Republic had done some very clever things with old technology—the Frankens blowing drones out of the sky with a basement-workshop maser kept coming to mind—but sooner or later the habit of trying to push technology into reverse gear was going to collide catastrophically with the latest round of scientific or technical breakthroughs, with or without military involvement, and leave the Lakelanders with the hard choice between collapse and a return to the modern world.

A week earlier, I probably would have considered that a good thing. As the train rolled into Defiance, I wasn’t so sure. The thing was, the Lakeland Republic really had managed some impressive things with their great leap backward, and in a certain sense, it was a shame that progress was going to steamroller them in due time. Most of the time, people say “progress” and they mean that things get better, but it was sinking in that this wasn’t always true.

I picked up a copy of that day’s Toledo Blade from a newsboy in the Defiance station, and used that as an excuse to think about something else once I boarded the train back to Toledo. The previous day’s drone shoot was right there on page one, with a nice black and white picture of Maude Duesenberg getting her sixth best-of-shoot trophy, and a big feature back in the sports section with tables listing how all the competitors had done. I didn’t pay attention to anything else on the front page at first, though, because another satellite had been hit.

The Progresso IV and the the Russian telecom satellite were bad enough, but this one was a good deal worse, because it was parked in a graveyard orbit—one of the orbital zones where everybody’s been sticking their defunct satellites since it sank in that leaving them in working orbits wasn’t a good plan. There’s a lot of hardware in most of the graveyard-orbit zones, and though they’re well away from the working orbits that doesn’t really matter once you get a Kessler syndrome started and scrap metal starts spalling in all directions at twenty thousand miles an hour. That was basically what was happening; a defunct weather satellite had taken a stray chunk of the Progresso IV right in the belly, and it had just enough fuel for its maneuvering thrusters left in the tanks to blow up. A couple of amateur astronomers spotted the flash, and the astronomy people at the University of Toledo announced that they’d given up trying to calculate where all the shrapnel was going; at this point, a professor said, it was just a matter of time before the whole midrange was shut down as completely as low earth orbit.

That was big news, not least because the assault drones I’d watched people potshotting out of the air depend on satellite links. Oh, there are other ways to go about controlling them, but they’re clumsy compared to satellite, and you’ve also got the risk that somebody will take out your drones by blocking your signals—that’s happened more than once in the last couple of decades, and I’ll let you imagine what the results were for the side that suddenly lost its drones. Of course that wasn’t the only thing that was in trouble: telecommunications, weather forecasting, military reconnaissance, you name it, with the low orbits gone and the geosynchronous going, the midrange orbits were the only thing left, and now that door was slamming shut one collision at a time.

It occurred to me that the Lakeland Republic was one of the few countries in the world that wasn’t going to be inconvenienced by the worsening of the satellite crisis. Still, I told myself, that’s a special case, and paged further back. The rest of the first section was ordinary news: the Chinese were trying to broker a ceasefire between the warring factions in California; the prime minister of Québec had left on a state visit to Europe; the melting season in Antarctica had gotten off to a very bad start, with a big new iceflow from Marie Byrd Land dumping bergs way too fast. I shook my head, read on.

Further in was the arts and entertainment section. I flipped through that, and in there among the plays and music gigs and schedules for the local radio programs was something that caught my eye and then made me mutter something impolite under my breath. The Lakeland National Opera was about to premier its new production of Parsifal the following week, and every performance was sold out. Sure, I mostly listen to classic jazz, but I have a soft spot for opera from way back—my grandmother was a fan and used to play CDs of her favorite operas all the time, and it would have been worth an evening to check it out. No such luck, though: from the article, I gathered that even the scalpers had run out of tickets. I turned the page.

I finished the paper maybe fifteen minutes before the train pulled into the Toledo station. A horsedrawn taxi took me back to my hotel; I spent a while reviewing my notes, got dinner, and made an early night of it, since I had plans the next morning.

At nine-thirty sharp—I’d checked the streetcar schedule with the concierge—I left the hotel and caught the same streetcar line I’d taken to the Mikkelson plant. This time I wasn’t going anything like so far: a dozen blocks, just far enough to get out of the retail district. I hit the bell just before the streetcar got to the Capitol Atheist Assembly.

Half a dozen other people got off the streetcar with me, and as soon as we figured out that we were all going the same place, the usual friendly noises followed. We filed in through a pleasant lobby that had the usual pictures of famous Atheists on the walls, and then into the main hall, where someone up front was doing a better than usual job with a Bach fugue on the piano, while members and guests of the Assembly milled around, greeted friends, and settled into their seats. Michael Finch, who’d told me about the Assembly, was there already—he excused himself from a conversation, came over and greeted me effusively—and when I finally got someplace where I could see the pianist, it turned out to be Sam Capoferro, the kid I’d seen playing at the hotel restaurant my first day in town. He gave me a grin, kept on playing Bach.

We all got seated eventually. What followed was the same sort of Sunday service you’d get in any other Atheist Assembly in North America: the Litany, the lighting of the symbolic Lamp of Reason, and a couple of songs from the choir, backed by Capoferro’s lively piano playing. There was a reading from one of Mark Twain’s pieces on religion, followed by an entertaining talk on Twain himself—his birthday was coming up soon, I thought I remembered. Then we all stood and sang “Imagine,” and headed for coffee and cookies in the social hall downstairs.

“Anything like what you get at the Philadelphia Assembly?” Finch asked me as we sat at one of the big tables in the social hall.

“The music’s a bit livelier,” I said, “and the talk was frankly more interesting than we usually get in Philly. Other than that, pretty familiar.”

“That’s good to hear,” said a brown-skinned guy about my age, who was just then settling into a chair on the other side of the table. “Even with the borders open, we don’t have anything like the sort of contacts with Assemblies elsewhere that I’d like.”

“Mr. Carr,” Finch said, “this is Rajiv Mohandas—he’s on the administrative council here. Rajiv, this is Peter Carr, who I told you about.”

We shook hands, and Mohandas gave me a broad smile. “Michael tells me that you were out at the annual drone shoot Friday. That must have been quite an experience.”

“In several senses of the word,” I said, and he laughed.

We got to talking, about Assembly doings there in Toledo and back home in Philadelphia, and a couple of other people joined in. None of it was anything out of the ordinary until somebody, I forget who, mentioned in passing the Assembly’s annual property tax bill.”

“Hold it,” I said. “You have to pay property taxes?” They nodded, and I went on: “Do you have trouble getting Assemblies recognized as churches, or something?”

“No, not at all,”

Mohandas said. “Are churches still tax-exempt in the Atlantic Republic? Here, they’re not.”

That startled me. “Seriously?”

Mohandas nodded, and an old woman with white hair and gold-rimmed glasses, a little further down the table, said, “Mr. Carr, are you familiar with the controversy over the separation of church and state back in the old Union?”

“More or less,” I said. “It’s still a live issue back home.”

She nodded. “The way we see it, it simply didn’t work out, because the churches weren’t willing to stay on their side of the line. They were perfectly willing to take the tax exemption and all, and then turned around and tried to tell the government what to do.”

“True enough,” Mohandas said. “Didn’t matter whether they were on the left or the right, politically speaking. Every religious organization in the old United States seemed to think that the separation of church and state meant it had the right to use the political system to push its own agendas—”

“—but skies above help you if you asked any of them to help cover the costs of the system they were so eager to use,” said the old woman.

“So the Lakeland Republic doesn’t have the separation of church and state?” I asked.

“Depends on what you mean by that,” the old woman said. “The constitution grants absolute freedom of belief to every citizen, forbids the enactment of any law that privileges any form of religious belief or unbelief over any other, and bars the national government from spending tax money for religious purposes. There’s plenty of legislation and case law backing that up, too. But we treat creedal associations—”

I must have given her quite the blank look over that phrase, because she laughed. “I know, it sounds silly. We must have spent six months in committee arguing back and forth over what phrase we could use that would include churches, synagogues, temples, mosques, assemblies, and every other kind of religious and quasireligious body you care to think of. That was the best we could do.”

“Mr. Carr,” Finch said, “I should probably introduce you. This is Senator Mary Chenkin.”

The old woman snorted. “‘Mary’ is quite good enough,” she said.

I’d gotten most of the way around to recognizing her before Finch spoke. I’d read about Mary Chenkin in briefing papers I’d been given before this trip. She’d been a major player in Lakeland Republic politics since Partition, a delegate to their constitutional convention, a presence in both houses of the legislature, and then the third President of the Republic. As for “Senator,” I recalled that all their ex-presidents became at-large members of the upper house and kept the position until they died. “Very pleased to meet you,” I said. “You were saying about creedal associations.”

“Just that for legal purposes, they’re like any other association. They pay taxes, they’re subject to all the usual health and safety regulations, their spokespeople are legally accountable if they incite others to commit crimes—”

“Is that an issue?” I asked.

“Not for a good many years,” Chenkin said. “There were a few cases early on—you probably know that some religious groups before the Second Civil War used to preach violence against people they didn’t like, and then hide behind freedom-of-religion arguments to duck responsibility when their followers took them at their word and did something appalling. They couldn’t have gotten away with it if they hadn’t been behind a pulpit—advocating the commission of a crime isn’t protected free speech by anyone’s definition—and they can’t get away with it here at all. Once that sank in, things got a good deal more civil.”

That made sense. “How’s the Assembly doing financially, though, with taxes to pay?”

“Oh, not badly at all,” said Mohandas. “We rent out the hall and the smaller meeting rooms quite a bit, of course, and this room—” He gestured around us. “—is a school lunchroom six days a week.” In response to my questioning look: “Yes, we have a school—a lot of,” he grinned, “creedal associations do. Our curriculum’s very strong on science and math, as you can imagine, strong enough that we get students from five and six counties away.”

“That’s impressive,” I said. “I visited a school out in Defiance County yesterday; it was—well, interesting is probably the right word.”

“Well, then, you’ve got to come tour ours,” Chenkin said. “I promise you, there’s no spectator sport in the world that matches watching a class full of fourth-graders tearing into an essay that’s been deliberately packed full of logical fallacies.”

That got a general laugh, which I joined. “I bet,” I said. “Okay, you’ve sold me. I’ll have to see what my schedule has lined up over the next few days, but I’ll certainly put a tour here on the list.”

“Delighted to hear it,” Mohandas said.

I wrote a note to myself in my pocket notebook. All the while, though, I was thinking about the future of the Lakeland Republic. Unless the science and math they taught was as antique as everything else in the Republic, how would the kids who graduated from the Assembly school—and equivalent schools in other cities, I guessed—handle being deprived of the kinds of technology bright, science-minded kids everywhere else took for granted?

***********

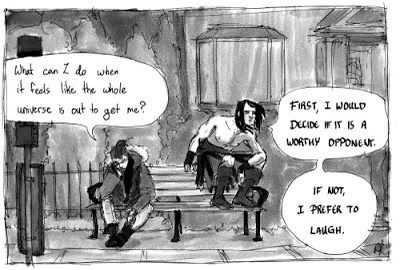

While we’re on the subject of narrative fiction, Conan the Cimmerian, Robert E. Howard’s archetypal barbarian hero, has made more than one previous appearance on this blog. With that in mind I’d like to point interested readers in the direction of one of Conan’s more wryly amusing modern manifestations. By Crom! by cartoonist Rachel Kahn features the guy from Cimmeria offering helpful advice for modern urban life. Those who find that thought appealing might consider visiting the publisher’s website here to read the online version or buy PDF copies of the two By Crom! books; those who want printed copies can find the Kickstarter for that project here.